Recent articles on wound therapy & healing

"The bloody patent battle over a healing machine"

This story is from the November 12, 2012 issue of Fortune.

FORTUNE -- A patent royalty is a beautiful thing. It is so much sweeter than found money because it is more than just good luck. It means that one party is paying another to use an invention. And before the lawyers got to arguing over claim constructions and prior art, before the government regulators and hospitals screamed enough was enough, and before the Russians came to Texas to explain Soviet-era library policies, there were few things more beautiful or lucrative in the world of patent royalties than the VAC.

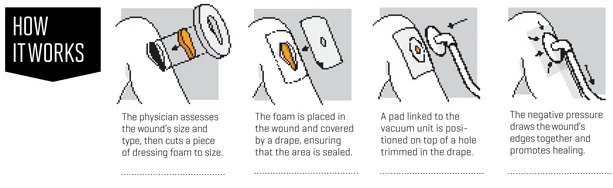

It's pronounced "vack" and stands for vacuum-assisted closure. Here's what it is: You cut a piece of foam to size and place it in a wound as a barrier and protector. Then you cover the wound and seal it up. One end of a tube goes through the seal and the other goes into a small pump. The pump produces negative pressure, creating an even vacuum through the foam, and the wound is pulled together and heals. If it sounds simple, it's because it is simple.

For much of the past 20 years this device was controlled by a San Antonio company called Kinetic Concepts Inc. The VAC transformed KCI from a second-tier medical manufacturer into a global juggernaut.

For Wake Forest University, which licensed the VAC patents to KCI, the device has meant about $500 million in royalties. Based almost entirely on the VAC deal, the university was ranked fifth by the Association of University Technology Managers in its most recent survey of licensing income, trailing only Columbia, New York University, Northwestern, and the University of California system. In recent years the KCI payments have propped up the bottom line of the university's medical center, and the VAC money has paid for research, recruiting, and construction that probably wouldn't have happened otherwise.

As you might imagine, all that success gave KCI and Wake Forest a powerful incentive to build a fence, to protect the patents at all cost. And it gave everybody else an equally powerful incentive to find a way through the fence.

MORE: Bad to the bone - a medical horror story

This is the story of what happens when there are billions of dollars wrapped up in a prosaic piece of technology that at its core is closer to your kid's science-fair entry than the Human Genome Project, one that despite all the commercial success and some 4 million or so patients still has its share of doubters in the medical community. It's a story about luck and timing and the squeezing of the health care dollar. It is about betrayal and wrangling over patents. And mostly it is about invention, the tenuous and uncertain act of breathing life into an idea that may or may not have been yours all along.

Dr. Louis Argenta says he invented the VAC, and he has the patents to prove it. He's a plastic surgeon at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, N.C., but is quick to point out that he isn't that kind of plastic surgeon. He deals with messy and nasty injuries that often can't or won't heal on their own. One night in the late 1980s, he was lying in bed and unable to sleep. He was reading The Gulag Archipelago and was worried about a patient who was slowly dying from an infected wound that couldn't be closed with surgery because the stitches would make things worse. "And, just suddenly," he would say later, "the concept of just using a giant vacuum -- we had played with vacuums in the laboratory a little bit, but this was the concept of using a giant vacuum to pull this whole thing together." He sketched a rough drawing in the margins of his book, and his wife told him to go back to sleep.

The next morning he talked to his lab manager, Michael Morykwas, a biomedical engineer, and they began working on a prototype. They tried it with success on pigs. But before they could put a device on a patient, they needed the approval of the hospital's ethics committee, which hemmed and hawed but eventually consented. The primitive VAC, Argenta would say, saved his patient's life.

For the next few years Argenta and Morykwas tinkered with their invention. In 1991 the university applied for a patent on their behalf and began shopping the device around. Wake Forest agreed to pay them half of any royalties, which to date has meant about $120 million apiece. But back then, getting rich seemed like a pipe dream. The leading medical journal for plastic surgery rejected a paper on their research, and there was little interest from the health care industry's biggest players. A licensing deal was struck in 1993 with KCI, which had a business renting and selling medical beds with air chambers. It already had products that used pumps. This would be one more. The first VAC hit the market in 1995, two years before the patents were granted and any research was published.

Negative pressure is suction, and suction has long been used to drain wounds and draw infections to the surface. What's different in wound therapy is that the pressure is maintained. Before the VAC came on the scene, the prevailing belief was that long periods of suction would damage the healthy skin that surrounds a wound.

MORE: The great stem cell dilemma

By 1999, KCI had built a $50-million-a-year VAC business through word of mouth, a go-go sales force, and top-notch customer service. That's nothing to sneeze at, but it was only the beginning. In late 2000, Medicare began reimbursing for the use of the VAC, and suddenly a therapy on the fringes came with its own revenue stream as doctors used the devices to treat diabetic ulcers and pressure sores. With the government's seal of approval, VAC revenue climbed to nearly $500 million by the end of 2003, on the way to becoming a billion-dollar product line.

That brought the money. Respect came in the field hospitals for U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In clinical language, the immense destruction caused by an improvised explosive device, or IED, is referred to as a high-energy soft-tissue injury. These can be devastating wounds, prone to infection and hard to close. Slight variations in healing can mean the difference in whether or where a limb is amputated. Dr. Chris Coppola operated on these wounds during two trips to Iraq. The dust and sand swirled everywhere, forcing the surgeons to use shipping containers as ORs. The VAC became such a critical part of their treatment that the medical staff pushed the military brass to give the device quick clearance for use during the airlift of wounded soldiers from the field to hospitals in Germany.

"We got our Ph.D. in the VAC over there," Coppola says, and there is little enthusiasm in his voice when he remembers this education. Now a pediatric surgeon in Danville, Pa., Coppola has written two memoirs of his time in Iraq, and he was one of the authors of a widely circulated medical journal article on the use of the VAC for treating traumatic injuries. "Little by little we gain knowledge," he says, "and it's a quite sad reality that we learn more about surgery and trauma during the years of war than we do in the time between wars."

It is not surprising that a low-tech product with such a fantastic combination of margin and mission would attract attention from competitors. Medical devices are particularly vulnerable to being copied because, unlike pharmaceuticals, the patents tend to build on previous discoveries and they don't rely on a unique molecule. And over time, as a company fights to hold on to its patents, it is forced to draw an ever sharper line between what's covered by the patent and what isn't.

The first chink in KCI's armor came in 2006, when a small company named BlueSky won the right to sell a competing product that used gauze instead of foam dressings. Other companies rushed into the market, including the British health care giant Smith & Nephew, which snatched up BlueSky and began planning a larger challenge.

Most doctors preferred foam dressings over gauze. The foam version was tested and proven, backed by years of KCI's research. So as Smith & Nephew and others sought to break KCI's lock, it became clear that they would need to offer foam dressings, and to do that they would have to show that the device of Lou Argenta and Mike Morykwas didn't really deserve patent protection, that the two men may have thought they invented the VAC but had really done no such thing.

At the heart of much of patent litigation is the concept of prior art: whether earlier research or invention makes a patent invalid. It can be tricky terrain because researchers -- particularly in that distant era before the web brought everything to our desktop -- aren't always aware of everything in their discipline.

MORE: Nu Skin and the short-sellers

If you are a patent attorney hunting for undiscovered prior art on wound care, the place to search is Russia, which had both a tradition of innovation in this area and its own war in Afghanistan in the 1980s to push surgical advancements. That's how, in 2008, Smith & Nephew found the research of Nail Bagaoutdinov, who had been a surgeon in Kazan, a provincial capital some 500 miles east of Moscow. In 1985 he began using negative pressure -- including foam dressings -- to treat infected wounds. A year later he wrote a brief paper on the results. This was the prior art that Smith & Nephew had been looking for. In late 2008 the company began selling foam-based therapy in the U.S., eager for a court fight.

Dr. Nail Bagaoutdinov began using negative pressure to treat wounds at a hospital in Kazan, Russia, in 1985.

KCI obliged, and the battle moved to a federal courtroom in San Antonio. KCI tried to exclude Bagaoutdinov's work, arguing that the decay and disarray of the Soviet Union's library system meant that the research fell into an abyss known as "gray literature" and didn't qualify as prior art. Smith & Nephew countered with its own experts, including a top deputy of the Russian Federation's Department of Libraries, flown into Houston to be deposed.

KCI lost the argument, and Bagaoutdinov's work was allowed at trial. He testified about his research and how he had tried to get a patent, or what in the Soviet Union was called an inventor's certificate. But he said his request was rejected because his invention too closely resembled the Bier Cup -- a glass cup attached to a tiny hand pump -- which has been around since the 1890s.

In March 2010 the jury rejected Smith & Nephew's arguments and said that KCI's patents were still valid, at least in the U.S. But eight months later the verdict was set aside. The patents, wrote Judge Royal Furgeson, were invalid based on the concept of obviousness, meaning that a person with skill in this area could have taken the existing research and arrived at the VAC. "The Bagaoutdinov references, while they may not have been easily accessible to the inventors, disclose almost all the claims asserted," his ruling said.

KCI and Wake Forest filed a notice of appeal, and they started figuring out how to maintain market share in a new environment, one where there was no monopoly and customers knew it.

Smith & Nephew, a company with annual sales of $4.2 billion, has been a global player in bandages and wound care for years, but Thomas Dugan, the president of its North American wound-care business, said the company struggled to find traction in the negative-pressure market. "We didn't have foam dressings. We just had gauze," Dugan says. "We were in there, putting our feet in the water, learning a lot, getting beat up a little bit, and then as we progressed, we obviously extended our presence as we got into the foam market. And that's what really started to open up the opportunity."

That opportunity, the competition in pricing and products, brought growth in KCI's VAC business to a halt. Since 2008 it has been stuck at about $1.4 billion in annual revenue. At trial, Dr. Jim Leininger, the company's founder, grimly recited the list of customers who had already abandoned the VAC for less expensive systems. There were hospitals in Laredo, Texas, and Memphis and Nashville, and nursing homes in Texas and beyond. Each of these switches underscored the scramble among both health care providers and suppliers to protect their bottom lines.

MORE: The robot doctor will see you now

One of the most bitter fights has taken place at San Antonio's University Hospital, which occupies a sprawling campus just a few miles from the KCI Tower. University Hospital gets a third of its revenue from the taxpayers of Bexar County, and it is pushing hard and with considerable success to transform itself from the area's public hospital to an institution that attracts more affluent -- i.e., better insured -- patients.

University was an early adopter of the VAC, but the relationship soured as costs increased. In 2009 the hospital spent $2.2 million on VAC expenses -- a third more than in the previous year -- at a time when it was feeling a squeeze from all directions. Moreover, it was getting little sympathy or relief from KCI.

"We were spending a lot of money, and it was becoming very expensive for the health system, these wound VACs, and we were getting direction from the C-suite that we needed to find a way to minimize the bleeding, if you will," says Francine Crockett, the hospital's vice president of supply-chain management.

Her team brought in another vendor, a company called Innovative Therapies Inc., which had been started in 2006 by former KCI employees. It uses a competing patent developed in Sweden in the 1970s that had languished until KCI made negative pressure a commercial success.

KCI has sued Innovative Therapies, alleging patent infringement and the violation of confidentiality and noncompete agreements. The litigation is still pending.

"This is bullyism," says Richard Vogel, Innovative Therapies' president. "It's a patent that should never have been issued, because it's anticipated by all sorts of prior art, but you have a right to that patent, and you are going to declaim loudly to the world that these are your patents, you own this space, and you are going to bully anybody and everybody into submission. And what's more, you actually do it. You will spend tens of millions of dollars beating up on small companies and on large companies. You'll sue customers. You'll sue doctors. Well, after a while, people just throw up their hands and say, 'We don't want to have to deal with this.' And to a large extent, that's what happened."

Beginning in 2010, the surgical-supply cabinets at University started carrying both KCI and ITI pumps and materials, and the upstart quickly gained a third of the business while officials evaluated the products. The hospital recently gave ITI single-vendor status for most of its operations.

Health care spending doesn't exist in isolation, and one treatment can often prevent a more expensive expenditure at a later date. But it's not often that providers get credits from payers for avoiding a future expense. Doctors like negative pressure because they can discharge patients sooner and don't have to change bandages as frequently. But as Medicare's negative-pressure payments grew from $24 million to $164 million per year between 2001 and 2007, the agency wasn't looking only at the length of stay. It just saw an exploding line item with a huge markup. Pumps were being reimbursed at an average annual price of $17,000, about four times what suppliers paid for the equipment.

MORE: Fantastic voyage - medicine's tiny helpers

In 2009, Medicare cut negative-pressure reimbursements by 9.5%. Now it's rolling out competitive bidding in the industry, having companies vie for the right to sell pumps in some of the nation's largest markets.

As part of that process, the government tried to answer some key questions. First, were foam dressings better than gauze? And second, was there any difference between the devices? KCI had claimed there were differences on both counts, with the hope of getting its own billing code -- and reimbursement rate. A report commissioned for the Department of Health and Human Services said there were no differences.

But the wound healers may have bigger problems. The government's report also contained this finding: "None of the high-quality reviews concluded that negative-pressure wound therapy provided additional benefit when compared to other interventional treatments."

Dr. William Lineaweaver is a Mississippi plastic surgeon who specializes in burn reconstruction and is the editor of the Annals of Plastic Surgery, which 15 years ago published the first research paper on the VAC, in a sense paving the way for all that was to happen by reporting that the device promoted healing.

Expansion of the Comprehensive Cancer Center at Wake Forest’s Baptist Medical Center. The school has collected nearly $500 million in royalties on VAC patents.

Lineaweaver wasn't the editor then, but he dismisses negative pressure as overused and unvalidated, a patient-management tool that is less about healing wounds than about cutting surgical costs. "It took advantage of the fact that reconstructive surgery has more and more to offer but is being reimbursed less and less," Lineaweaver says.

There is plenty of evidence that negative pressure works by increasing blood flow and encouraging the formation of healthy tissue. But the research studies tend to be anecdotal, unlike the randomized trials that might be required of a drugmaker to gain FDA approval. The industry has told the government that it needs to look beyond clinical data and pay more attention to expert opinions and compelling observational studies.

In August the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit reversed Judge Furgeson's invalidation ruling and sent the case back to San Antonio. The patents are still valid, for now. But KCI was by then no longer a party to that action. Instead of joining with Wake Forest in protecting the patents, as it first said it would do, the company reversed course and said the ruling from Texas -- along with similar rulings in Europe -- had freed it from the licensing agreement because there were no valid patents to license. Its last royalty payments, of $86 million, were in 2010. The patents expire in 2014. Wake Forest and KCI have gone to court, each accusing the other of acting in bad faith.

KCI said the university was dragging its feet on arbitration and wanted an exorbitant payout of more than $200 million for what courts here and in Europe had ruled were invalid patents. Wake Forest said KCI had abandoned its partner at a time of need, had been shorting it on payments for two years, and had timed its legal action to squeeze inside a deadline of having to pay a semiannual royalty payment of more than $40 million.

Wake Forest officials declined to be interviewed but released a short statement saying the university was pleased with the appellate court's ruling and intended to enforce its patents against those using them without compensating the university. (Update: On Nov. 1, Smith & Nephew said it had reached a settlement with Wake Forest. The full terms weren't disclosed, although the company's third-quarter results and discussion with analysts suggest the agreement cut into profit by around $8 million and wouldn't have a significant long-term impact on its wound-care business.)

John Bibb, the general counsel for KCI, says, "I wouldn't say the relationship deteriorated so much as the strength of the patent portfolio, frankly, deteriorated. If you think about it from the context of the commercializing company, it's hard to pay royalties for patents that have been invalidated everywhere they've been asserted."

KCI was bought in 2011 for $6.3 billion by a private equity firm, Apax Partners, along with two Canadian pension funds, an arrangement that gives it the ability to retool and reinvest out of the glare of Wall Street. Shortly after the deal closed, Apax moved in a new management team, replacing KCI's chief executive and the head of its global VAC business. Joe Woody, the new chief executive, spent six years at Smith & Nephew and was one of the architects of the company's assault on KCI's dominance. He says that despite that history, he's gotten a warm reception as he repositions KCI to move past the days of product exclusivity. That means cutting costs, being sensitive to price, and keeping the focus on innovation and customer service as the company tries to grow here and abroad, where diabetes and related circulation problems are surging.

"The competitive environment is much like any other medical device company would face now that we have patents that are invalidated and we are in a different market position," Woody says.

MORE: WellPoint's high-tech reboot

With all that's happened, including shifts in a legal position that had been at the core of KCI's corporate culture, I asked Woody and Bibb whether the Wake Forest patents should have ever been granted by the U.S. Patent Office. The line went quiet, and after an awkward period of silence, a spokesman said it was a speculative question and time to move on.

Not that long ago, an MIT student came out with a prototype for a hand-powered negative-pressure pump that she said could sell for $3 and be a boon in the developing world, where most people can't afford the Cadillac-priced products of Western health care. Perhaps unsurprisingly, amid the praise for her resourcefulness was ridicule that she had done little more than cobble together a device from products found at a hardware store.

That's the argument used against the VAC, and it both misses and is exactly the point. Maybe the VAC was there all along, just waiting to be found. But somebody had to find it and -- more to the point -- claim ownership. The patents gave the idea value, and the value helped create a market, and the market created fortunes. KCI's founder, Jim Leininger, is a billionaire. Lou Argenta and Mike Morykwas have split about $250 million in royalties, and Wake Forest's portion has helped build its campus and its reputation. And then there is one more inventor, a Kansas doctor named David Zamierowski, who received more than $200 million from KCI. His patents on the use of negative pressure predated the VAC and were licensed in part as a precaution, just to be safe -- a fence around the fence.

Nail Bagaoutdinov never got inside that fence. He just helped tear it down. For his time, Smith & Nephew paid him $350 an hour, far less than the million-dollar bonus he originally sought.

He left Russia in 1995 and emigrated to the U.S., where he learned English so he could continue to practice medicine. Like many doctors born overseas, he now works in rural America, rotating through emergency rooms in eastern Kentucky. When we talked, he had just come off a night shift and apologized for being tired.

There was no bitterness in his voice about what might have been, and he said he was surprised when his work became the central piece of evidence in patent trials around the world.

"Negative pressure, it's not complicated," he said.

Bagaoutdinov doesn't claim to be the inventor of the VAC. To this day he has never used one. His device was a much cruder affair. He said he thought he had come up with something new, but there was no way to know for sure. At the time, he was just a surgeon at Kazan City Hospital No. 8 and was unable to take his idea to the next step.

This story is from the November 12, 2012 issue of Fortune.